Martian War Chronicles: Population of Loss

The Lost Boy

A tale of Fey and Spirits and those left behind.

The streets of Woking were crowded that Saturday afternoon, much more so than usual owing to the commotion in the sandpits outside of town. There, the boffins and such folk as didn’t have enough business of their own to mind had gathered to gawk at a great cast-iron capsule fallen from the sky. Some knaves chattered ridiculously that it had come from the planet Mars, and some others were fool enough to believe them. Most sensible people agreed that it was a shell launched by that giant German gun, a boast from the Kaiser that Her Majesty was sure to answer in a way not to the liking of her churlish grandson.

Then there were a few people who hardly gave a thought to such matters, and one of them was a young lady – let’s call her Mary, as so many young ladies are, for no one knows her name for sure – a new mum, very pretty and proud of her baby boy, whom she pushed around in a cozy little pram. All her thoughts were on this little boy, who was born the previous Sunday eve, nearly a week old now, and was to be baptized tomorrow at old St. Peter’s, the church of his namesake.

Now, it was generally believed to be bad luck to take a child out before he was baptized, but Mary wasn’t raised to be superstitious, and this strong young girl had been cooped up in bed for too many days, and now that the weather was bright and sunny she felt she just must have some air, and it would do no good to go promenading without little Peter, since all of the neighbors would be asking about him. And she went alone, because her husband, a strapping young lieutenant in the 11th Hussars, had to be about on maneuvers.

Poor Mary might have been better off if she’d been a bit more superstitious, because she never made it home that day – or at least not the home she was expecting. But then again, many people in Woking who stayed in their homes and businesses fared no better, and expired in the flames or under collapsing timbers. It was the oily black smoke that did in Mary and her darling little boy, sadly unbaptized as I have already reported.

When the sun went down, the smoke had mostly cleared, and the bodies lay in the streets right where they first fell. For a little while there was no more commotion on the streets of Woking, and then, gradually, it returned. The rats came out, along with a few mewling cats to pester them. A riderless horse sometimes clopped by from the Common, and later on, when the moon rose high, mangy dogs with their stomachs clung to their ribs came on and had their unwholesome victuals. At midnight, the beasts were joined by other things that came around at such times as this, things without form or flesh – at least not the flesh you’re used to. Things that men saw only with great difficulty; things that, in these days, most men dismissed even though their ancestors huddled around bonfires in fear of them.

Now some of these creatures came from the worlds sidewise to this one, moving in wispy black shrouds that might have been cloaks, with bone-white fingers wrapped around translucent scythes that cut loose the struggling spirit from its shackle of flesh. Others were golden hued and rosy cheeked, and they blew on flutes or plucked lyres, and those trepidatious souls who had not already shuffled off were charmed into following. Some they led to good destinations, and others to not so good ones, but the weak, sickly spirit of little Peter they passed by. That forlorn numen could barely even peek outside the prison of his own eyes, through which he could only dimly see the other dead folks go marching.

Deep into the night, some other creatures came by – clad in form and flesh somewhat more like what you’re used to – and had a look around. They laughed a bit, and generally approved of the change.

“We haven’t had a walk around here in quite a long time,” one of them said. “It feels good to get my toes in this old dirt again.”

“Yes, but they’ve made quite a mess of this place,” said another.

Now these were wicked sounding words, but the creatures weren’t really wicked, no more than a bear or a lion is wicked. Cruel, perhaps, and certainly savage, but they lacked that divinely bestowed discernment that made man culpable for his sins. These creatures were the Fey.

“It’ll take a good long time to be put back to right,” agreed a third. “If they don’t come back.”

And they all had a look around, and some of them thought that maybe this time the men really wouldn’t come back. Then the world could return to what it used to be, back when it was still old, but young in their memory. For the Fey had lived in these isles when they were greener and more pleasant, before even the first brute men in shaggy cloaks trod across the dry English Channel.

A fairy of the Airish sort, a pixie with bright butterfly wings, fluttered over little Peter’s body and, for the first time that night, someone paid him notice.

Now this pixie was a girl, or at least a girlish sort of Fey, for sex, like the other human qualities they adopted, was more of something they aped rather than something they really possessed. And she had learned to ape some other human qualities in line with her sex, like sympathy, affection, and even a desire for motherhood. Like all fairy qualities, even the positive ones, these were not fully wholesome attributes, and so she didn’t react to the sight of poor Peter’s suffocating spirit the way a human would have. Instead, she felt a selfish delight, like a child who finds a discarded toy in the rubble of a burned down house.

“Come out, little boy!” she cooed as she bent down to his prison, and beckoned him out with her finger. Out rose his weakling spirit, slowly, cautiously. A breath of sweetness, a struggling flicker of light, an echo – little Peter’s numen was none of these things, but might remind you of each of them.

“That won’t do, little boy!” she giggled. “Don’t you know what you are? Don’t you know how to behave?”

The fairy danced around him and waved her arms and her wings, and he floated up like a feather. She teased and she breathed, she thought, and weaved, and pulled, and then little Peter’s numen was not a breath or an echo or a flicker of light anymore, but a definite shape and solidity, the makings of a body perhaps like the one he might have had if he had not choked on the black smoke, a body made of the same tenuous matter as the fey girl. Through the long night she helped him grow, and his head was covered with wild brown hair, and his clever eyes had color. And then, discovering he had a voice, he laughed with pure joy.

This little explosion sent the fairy reeling, and she felt as if she might grow herself, or sprout a new pair of wings. She laughed and cheered and scooped up Peter into her arms, cradling him against her bosom like his own mother might.

This racket didn’t go unnoticed, and some of the other Fey gathered to see what had happened. Most of them quickly lost interest, as they did with most things, but the few who stayed looked on disapprovingly. But whether their disapproval grew from a sense of violated propriety or from jealousy, no one can really say.

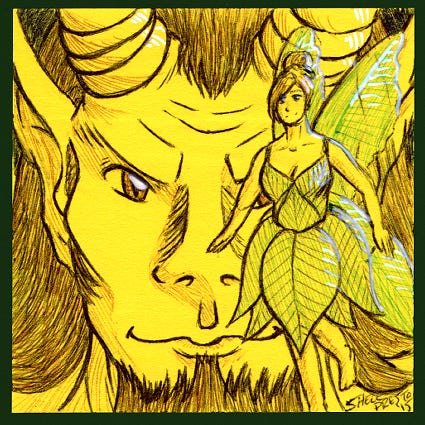

A satyr called out to the pixie, whose name in the Fey language sounded like the tinkling of a tiny, silver bell, and asked just what she thought she was doing.

“I’ve found a little boy! His name is Peter. He’ll be my son now, and I’ll be his mother,” she replied.

“You know you can’t do that, it’ll be the end of you! Leave him where you found him, for the psychopomps will be looking for him,” the other said.

“I can do what I want! This one hasn’t gone down to drown in the bright water, and the psychopomps already passed him over. He’s my son, and I am his mother now!”

The satyr's stern face frowned in disagreement. “That’s a man child. You’ll never be his mother."

And the fairy whose name sounded like the chiming of a tiny bell stomped her foot and shouted. “Fine! Who needs a mother, anyway? Nevertheless, he’s coming back with me, and we will do things that you’ve never imagined.” The pixie went about her business, picking through the rubble for things her little boy might like: a toy wooden sword, a peacock feather from a lady’s hat. In a flash of inspiration, she decided that he would need stories for his bedtime reading. In the ruins of a bookseller, she picked two volumes at random – not that it mattered, since she couldn’t read anyway – A General History of the Pyrates and Song of Hiawatha.

The satyr looked on and said nothing, but he was very troubled. No human child had ever been brought to their country, but he had heard of the trouble they caused whenever one had come to other realms in the Dreamscape. He had heard dreadful stories of how their minds, every bit as mercurial and capricious as the Fey, altered the very stuff of the Dreamscape at their whim, transforming it until there was nothing recognizable – until there was no room left for the Fey. In other words, just like the way things were here. Did she want there to be no place left for the Fey anywhere in Tellus? The satyr said all these things to her.

“I don’t care! I will do what I want, and so will he! And if there’s no place left for you, then it will be even better!” She laughed spitefully. “But I’ll give him your name so we can remember you when you’re gone! Peter Pan, I’ll call him!”

Dawn was coming, and there was no time left to dawdle; the gates of the Rampart were closing. The pixie soared into the twilight. Nestled in her arms, little Peter’s eyes were filled with mischief and cunning as he bid good bye to the world of his birth.

To read another exciting Martian War Chronicles story, check out The Devil to Pay below.

Or find other chapters and series at The Story Directory.